How to Use a Hacksaw

Metal isn’t hard to cut, and a hacksaw isn’t difficult to use. That’s not our opinion, that’s a fact. But with all the power tool options available today that cut metal, such as jig saws, reciprocating saws, circular saws, and abrasive wheel chop saws, you might ask whether you should bother with this old-school metalworking tool. There are several good reasons to learn how to use one: Hacksaws are simple devices that cut metal quickly, accurately, and quietly. They don’t have batteries that need to be charged. A small selection of blades will take you through an incredible range of work. Furthermore, hacksaws also cut ceramic tile and plastics.

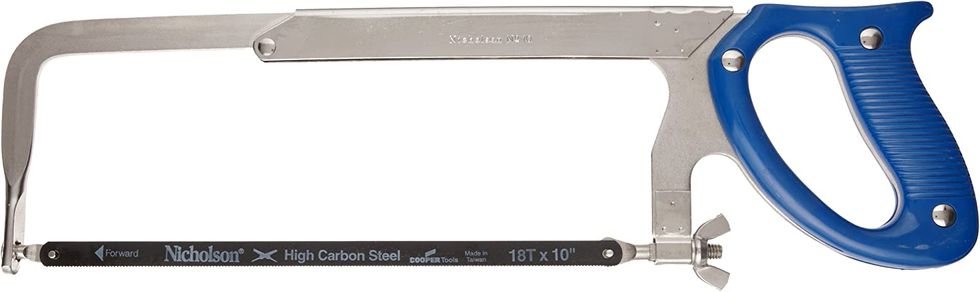

Below we show a few great hacksaws and blades, and explain the fundamentals of using this great tool.

Great Hacksaws And Blades

Hacksaw Basics

The immutable law of hacksaw knowledge boils down to this: Thick materials require a blade with fewer teeth per inch, while thin materials require a blade with more teeth per inch. Simple, right?

More From Popular Mechanics

The goal is two have a minimum of two hacksaw teeth in contact with the material, while not increasing the tooth contact to the point where the blade clogs with the waste particles that it is producing. That is, if you cut thick material (say a half inch thick) with a blade that has a large number of teeth per inch (say 24 or 32 teeth), you’ll find it tough going. The fine teeth become clogged with metal particles. It’s much easier to cut such a thick piece of metal using a blade with 14 or 18 teeth per inch. Teeth per inch is abbreviated as TPI.

The same holds true for cutting something thin, like sheet metal. If you try cutting that with a 14-tpi blade, you’ll find that the teeth will snag on it. The cut goes much more easily when you switch to a 32-tpi blade.

Common hacksaw blades are available with 14, 18, 24, and 32 teeth per inch. For metal that is in the vicinity of 1/16-inch thick and thicker, use a blade with 14 to 18 teeth per inch. For metal that is thinner, use a blade with 24 or 32 teeth per inch.

Hacksaw Hacks

Every hacksaw owner should take these hacks to heart. They’re few in number, but they’re important and will help you master the art and craft of cutting metal by hand.

The Three-blade Minimum

Three typical bi-metal blades will see you through virtually every cut you will need to make. If you intend to cut ceramic tile, buy a hacksaw blade with a tungsten-carbide grit cutting edge.

Use Oil

Metal workers argue about this incessantly, with people forming two camps—“oil” and “don’t oil.” I’m an oiler. People say that oil causes metal particles to stick to the blade. My response is that the metal particles will stick to the blade whether you oil or not. The issue is whether the particles will slide around more freely and whether the teeth themselves can slide more freely over the metal.

People worry about what oil they should use to lubricate their metal cutting. My response, as an oiler, is that almost any oil is better than no oil. The same motor oil that you use in your lawn mower (10W-30) will work. So will the bar and chain oil that you use in your chainsaw. If you use a thinner oil, such as spraying the cut with WD-40, you’ll find it will work, but it will be messy and you’ll need a lot of it.

If you’re cutting thick material, pause occasionally and add more oil to the cut surface and the blade. Use a disposable piece of shop towel to catch the runoff.

And if you really want to lubricate the cut properly, use a dedicated metal-cutting lubricant like Tap Magic.

Just remember to use a part cleaner or solvent to remove any trace of oil if you want to weld or paint the metal after cutting. Lubricant residue will prevent paint and weld metal from sticking, so scrupulously clean the cut metal with solvent such as a spray-on parts cleaner or degreaser.

Clean the Blade

Whether you lubricate the cut or not, metal particles stick to the blade, as does paint from the cut part, rust, accumulated carbon, and good old-fashioned dirt that somehow found its way onto the surface. Don’t put the hacksaw away until you flush the blade clean with spray lubricant.

Begin With an Angle, Finish Horizontally

When cutting square and rectangular bar stock (or square tubing) start with the saw held at an angle.

Once the angled starting cut is well established, move to a horizontal cut. If you start the cut by sawing horizontally, the saw will slide off the cut line.

Standard Versus High-tension Saws

A standard hacksaw holds the blade with relatively low tension. The blade is placed in the frame and tightened by turning a small wingnut at the rear of the frame.

Many hacksaws today are high-tension types. These saws are equipped with a blade-tensioning mechanism that exerts thousands of pounds of tensile force on the blade to hold it tightly in position. This enables the blade to last longer and make a straighter cut, particularly in tough or thick materials.

Installing a hacksaw blade is simple. Standard hacksaws use a simple mechanism (fit the blade in place and tighten the wingnut). High-tension hacksaws differ as to the tightening mechanism they use.

Installing a High-Tension Hacksaw Blade

Odd Jobs

Hacksaws excel at doing odd jobs that are difficult to do with other saws or even other tools. We list four of these oddball jobs here.

1. Cutting Bolts, Screws, and Studs

The only thing worse than being faced with a screw or bolt that is too short is one that is too long. How you cut these to length depends on whether you have a nut to thread over it.

But there’s also the challenge of cutting a fastener to length when there’s no nut available to protect the fastener.

Cutting the bolt, screw or stud to length can be tricky. You need to clamp it firmly in a bench vise.

2. Cutting Tile

A hacksaw can be equipped with an abrasive blade that allows you to cut ceramic tile.

3. Cutting Shims and Spacers

It’s not usual when building or repairing things to use a small spacer (shim) to align parts either so that they work properly or so that their appearance is more pleasing. But finding material for that can be tricky. Ordinary hardware store washers can be pressed into service either as they are or with some of their thickness removed on a bench grinder.

4. Cutting Slippery Materials

It can be difficult to get the saw started on slippery materials such as pipe with a bright galvanized finish or metal with an annodized finish. You may find that the saw blade doesn’t want to bite into the cut. Solve the problem by starting the saw in a notch.

Senior Home Editor

Roy Berendsohn has worked for more than 25 years at Popular Mechanics, where he has written on carpentry, masonry, painting, plumbing, electrical, woodworking, blacksmithing, welding, lawn care, chainsaw use, and outdoor power equipment. When he’s not working on his own house, he volunteers with Sovereign Grace Church doing home repair for families in rural, suburban and urban locations throughout central and southern New Jersey.