Why real estate is plummeting, but not everywhere.

This article is from Full Stack Economics, a newsletter about the economy, technology, and public policy.

In March 2021, a woman in the D.C. area put her house on the market and got 88 bids—including 76 all-cash offers and 15 from people who hadn’t bothered to visit the property in person.

“The offers just kept coming,” she told CNN at the time. “I’m thinking, ‘This is just out of control.’ ”

That frothy, oozing-over-the-top market has been over for a few months now, and new data suggest that we might be entering a very different type of housing market.

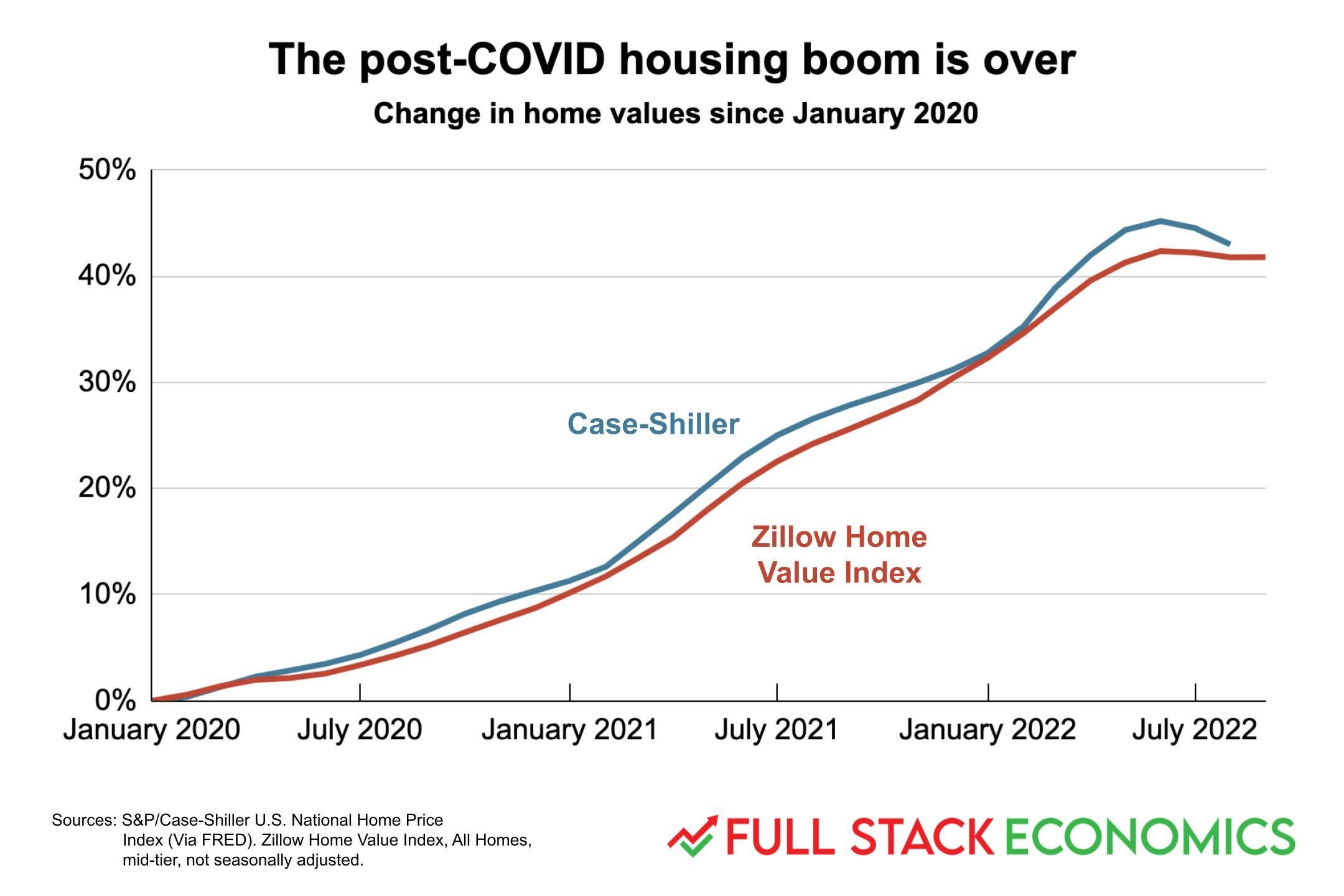

Home prices in the United States fell by 1.1 percent between July and August, according to new data from the Case-Shiller index. That’s by far the biggest monthly decline since the last housing crash hit bottom in 2012.

Another widely used index of housing prices, the Zillow Home Value Index, doesn’t yet show an outright decline. But it shows that home prices have been flat in recent months after two years of strong price appreciation.

Experts are becoming increasingly worried that we’re heading for a major housing correction.

A modest decline in home prices would be benign—even welcome, given how expensive housing has gotten in recent years. But a sharp decline in home prices could have some negative effects on the broader economy. Homebuilders might react by dramatically cutting back new home construction, which would not only throw thousands of people out of work but would worsen our long-term housing shortage.

A sharp decline in home prices could also trigger a wave of destabilizing defaults and foreclosures. And some experts think a big decline like that is a real possibility.

“My base case is something like a 10 percent drop in home prices relative to the peak,” said Arpit Gupta, a finance professor at New York University. But he said things could get much worse than that.

“A 30 percent drop in prices would not be super out of the ordinary if you take the level of volatility we’ve had for the last 20 years,” Gupta added. That would put the current housing bust on par with the crash that began in 2006 and triggered the Great Recession. Many experts blame rising mortgage rates. The average rate on a 30-year mortgage soared from 3.5 percent in January to around 7 percent today. These increases have dramatically raised the cost to buy a home.

On one level, the cooling housing market is an intended result of the interest rate hikes the Federal Reserve began back in March. Higher interest rates put downward pressure on the value of all assets, which is supposed to discourage spending and thereby reduce inflation.

What makes things especially tricky for the Fed is that the housing market is much less liquid than other major assets like stocks or bonds. It takes a couple of months for someone to sell their home, and then another month or two for sales to be reflected in national statistics. As a result, home prices tend to have more momentum than other assets. Once prices start to fall, they tend to keep going in the same direction.

This is arguably what happened during the Great Recession: The Fed’s effort to cool the booming housing market with rate hikes between 2004 and 2006 worked a little too well, ultimately producing a housing crash that lasted until 2012.

Most experts don’t think the U.S. financial system is as vulnerable as it was in 2008. But it’s very possible for declining home values to trigger a garden-variety recession.

East vs. West

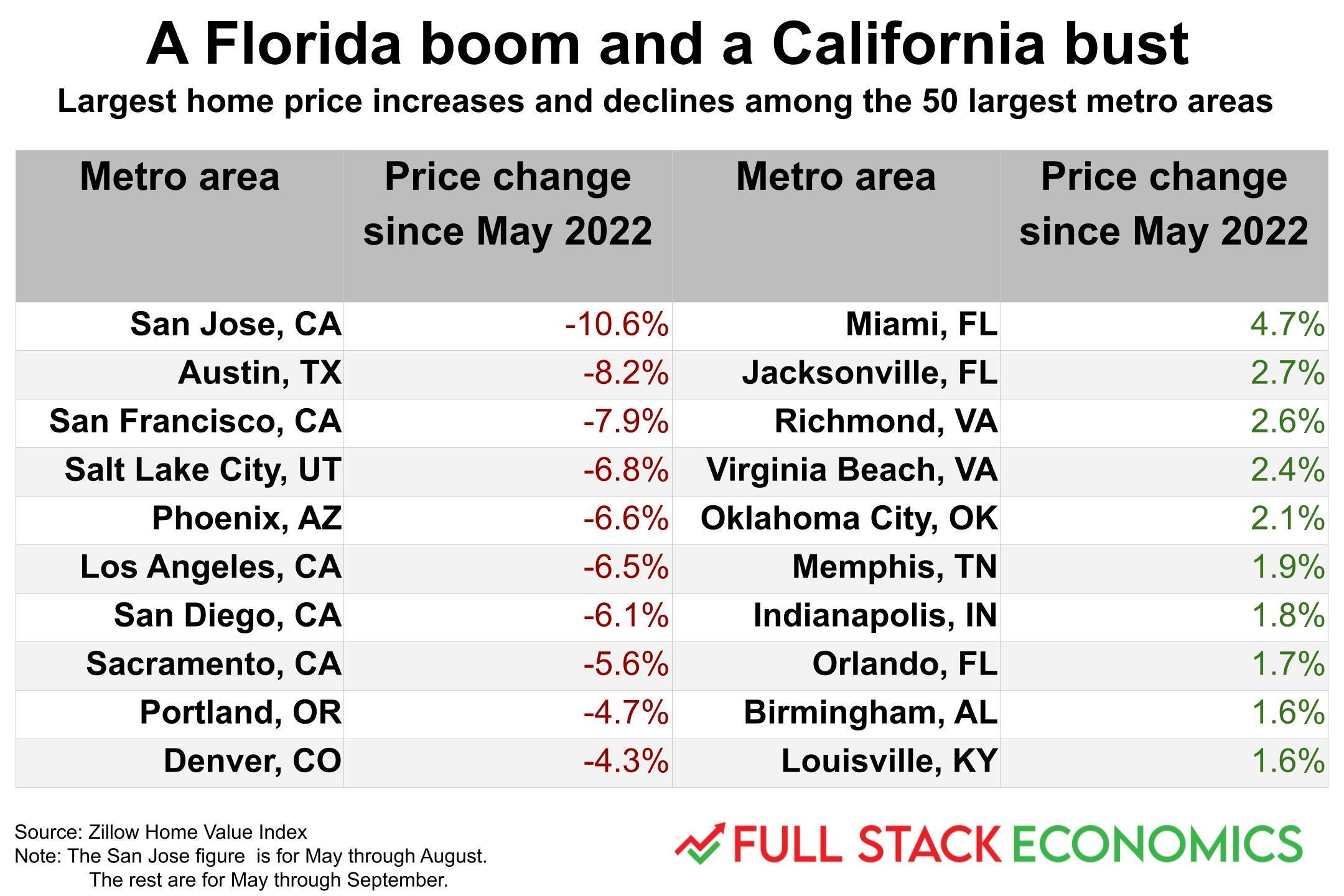

National averages mask significant variation at the metropolitan level.

Every one of California’s major cities—including Los Angeles, San Diego, and the Bay Area, some of the most expensive real estate markets in the country—has seen dramatic price declines over the last four months. Other Western and Southwestern cities, including Austin, Phoenix, Las Vegas, Portland, and Seattle, have also seen big drops.

At the other extreme, a number of Southern cities—especially in Florida—continued to enjoy substantial home price gains over the last four months. The Northeast and Midwest were somewhere in the middle, with Chicagoland homes losing 0.5 percent over the last four months and homes in the New York area gaining 0.7 percent.

While the regional pattern is clear, it’s not obvious why things are breaking down this way. Experts I talked to offered several possible explanations, but I didn’t find any of them fully convincing.

NYU’s Gupta argued that cities west of the Rockies have a history of housing volatility. The Phoenix and Las Vegas housing markets were famously rocky during the 2008 housing crash, for example. He blames this on a less flexible housing supply in these cities.

Two factors are significant here. First, Eastern cities tend to have older housing stock, which means more opportunity to expand the supply of housing by renovating or replacing older homes. Western cities lack this safety valve, and as a result they tend to see bigger booms when demand is strong, followed by sharper price declines when demand weakens.

The federal government also owns a ton of land in Western states, which limits how far cities can expand outward. Some Western cities also have urban growth boundaries. Again, a rigid housing supply can contribute to greater volatility on both the upside and the downside.

Falling home prices could also be connected to the pandemic and the resulting work-from-home trend. It may not be a coincidence that the three cities with the largest price declines—San Francisco, San Jose, and Austin—are all major centers for the tech industry. Seattle, another tech hub, has also seen a significant decline in home values.

Tech workers seem to have been particularly successful at resisting employer pressure to return to a physical office. Perhaps as tech workers realized they could work remotely indefinitely, they began to doubt whether it made sense to pay a big premium to live physically close to their employers.

Fortune housing reporter Lance Lambert suggested to me another possible tech connection: The falling values of many tech stocks could be reducing the amount of cash sloshing around West Coast housing markets.

There’s an obvious partisan ax someone could grind here: Most of the biggest losers are blue cities in blue states, while the winners are mostly smaller cities in red states. Maybe blue-state policies on COVID, crime, or something else are making those states less attractive places to live.

But I don’t think this withstands close scrutiny. Most obviously, Salt Lake City has seen faster home price declines than most other cities, and Utah isn’t a blue state. Las Vegas and Phoenix are located in swing states. On the flip side, home prices in New York City have held up better than those in Dallas, Houston, or Atlanta.

A YIMBY Housing Correction?

Another intriguing theory comes from the Mercatus Center’s Kevin Erdmann. In a recent post, he described declining property values in California as a “YIMBY housing correction.”

What he means is that the state has become increasingly aggressive about forcing cities to permit housing construction. For example, state law may soon force the wealthy beach town of Santa Monica to accept construction of thousands of new homes over the objections of local elected officials. California has also recently lifted restrictions on accessory dwelling units, eliminated parking mandates near transit stops, allowed duplexes to be built across the state, and much more.

If this blizzard of pro-housing legislation works as intended, California might finally start to address its severe housing shortage by building a bunch of new homes. And Erdmann argues that home prices in California are declining in anticipation of that new supply coming online in the coming months.

While this is a California-specific theory, it could also explain falling prices in neighboring states. For decades, home prices in cities like Phoenix, Las Vegas, and Portland have been buoyed by Californians fleeing that state’s high home prices. If California’s housing situation improves, the flow of housing refugees to neighboring states should slow, reducing upward pressure on home values across the region.

As a fan of pro-housing legislation, I would love for this to be true. But I’m skeptical on two levels. First, I’m still not sure that California has enacted strong enough policies to truly address its massive housing shortage. Second, I’m skeptical that the prospect of future home construction would have such a big impact on today’s home prices—some of these policies were only enacted in the last few months. But I’ll be keeping an eye out for further evidence—and, hopefully, much more housing coming online.

Most likely, a combination of factors explain the different home-price trajectories of West Coast, Northeastern, and Southern metropolitan areas. Patterns will hopefully become more clear as experts get more months of data to work with.

Unfortunately, the Federal Reserve doesn’t have the luxury of waiting for all the data to come in before making decisions, and one of its main jobs is crushing inflation that’s still way too high. The Fed’s Open Market Committee will meet next week to decide how much to raise short-term interest rates to try to fulfill that duty. Their decision could matter a lot for the home you’re trying to sell, the one you’re trying to buy, and the economy no one wants to see careen into the dumps.